My Summer Experience

My name is Max Wang, and I’m a third-year Computer Science student here at Clarkson with a minor in the humanities. This summer, I participated in a 10-week long data science research internship at the University of Vermont as part of the SOCKS (The Science of Online Corpora, Knowledge, and Stories) Research Internship program, which was hosted by UVM’s Complex Systems Center. SOCKS is a five-year project funded by the National Science Foundation that seeks to better understand how computational social scientists can harness the vast amounts of text data and archival information currently available online. It provides $20 million for funding various multi-year-long research projects and workforce and education development initiatives.

The SOCKS project ultimately aims to advance new theories and methodologies to measure sentiment and stories online. Some of these projects include: Can Twitter data tell us something about society’s happiness? Or can the content of one’s Instagram posts predict mental health illness? Other projects have ranged from “developing a hierarchical model for unraveling conspiracy theories,” to testing a “universal instrument for comparing complex systems” (I pretend I understand what this means). As another example, a future project I’m currently considering is seeing if there is a way to characterize at scale the sections of a privacy policy that disclose what information a company “collects,” “uses,” and/or “sells,” employing tools of natural language processing and web scraping to come up with a method. Tracking the flow of information might be important for increasing a company’s transparency in their disclosure of how they use people’s personal information.

The internship program was split into four teams: 1) Data ethics, privacy, and narrative bias (which was the team I was a part of), 2) Indigenous voices in global environmental governance, 3) Social and health narratives, and 4) Analysis of local news stories and programs.

The interns worked on projects ranging from identifying student-news partnerships in newspaper publication data, to identifying linguistic patterns online that might be associated with sentiments of trauma or resilience. 3 interns, including me, worked on the data ethics team, 4 were on the Indigenous voices team, 2 on the health narratives team, and 4 on the local news stories team.

I found out about the program by a simple Google search, I looked up REUs on Pathways To Science – an online directory of education and career opportunities in STEM – that dealt with developing technology through a social issues lens and I came across hundreds. I discovered this UVM internship along with about 6 other internships that sounded interesting and applied to them. The UVM internship was the only summer program that accepted me. I felt very lucky. I thought that opportunities to engage in that type of work — simultaneously interdisciplinary, humanities-related, tech-related — did not come easily.

What do I want? – Learning more about my interests

Throughout my summer internship, I had the pleasure of engaging in many interactions that captured my fascination and imagination.

Some learning moments among the many that I had:

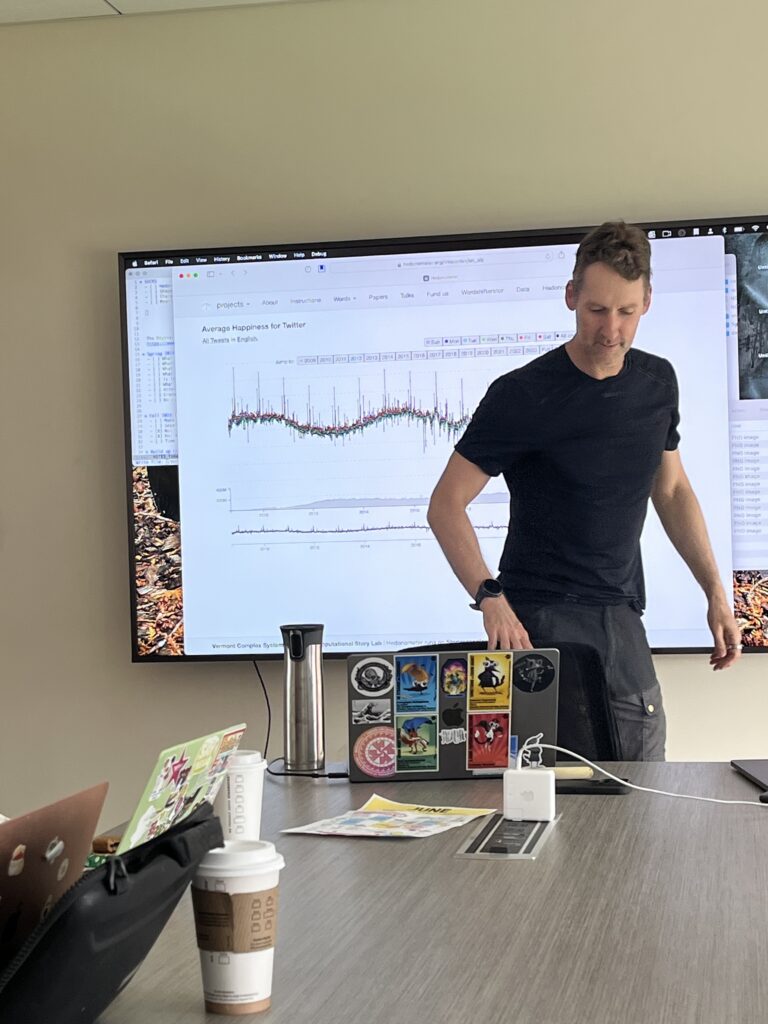

Dr. Peter Dodds, a professor in the Department of Computer Science at UVM, introduced me and my intern cohort to his research on the Hedonometer, a computational instrument that tries to measure societal well-being from tweets on Twitter. His research team tried attributing “happiness level scores” to certain words, calculated a general average score for each day between a specific time period, and then tried to see if results correlated with notable cultural events. I became curious about the ethics surrounding big data tools: Is this ethical? What if it’s genuinely impossible to truly gauge societal wellness from social media data? What were some limitations of the research?

My friend, Angela Kakaruk, presented her research on the current state of Indigenous participation in her hometown’s environmental governance. She studied the work of Native Conservancy, a Native-led kelp farm that promotes economic opportunity and champions the more than 3000 years worth of land stewardship knowledge and values of Native peoples in Alaska, providing a sustainable solution to the climate crisis.

She exposed the current fight between grassroots organizations and the government over the issue of carbon sequestration. She explained that carbon sequestration is a false solution to the climate crisis because 1) companies are sequestering carbon on lands that they are treating as a commodity, 2) because companies still emit carbon emissions but through technology required to build sequestration farms (and also something called artificial carbon sinks), and 3) demand for carbon credits — sometimes thought to discourage carbon emission production due to the cost of purchasing those credits — is actually increasing and companies just pay more to emit more.

Her work taught me that who has a “seat at the table” and who are the people with the power to pull levers (with money, influence, etc.) matters in the conversation about advancing sustainable climate solutions or, thinking more broadly, advancing equitable technologies.

Randall Harp, professor of Philosophy at UVM, served as one of my interlocutors for the summer and helped me better understand the complexity of privacy rights. I recall one particular interaction where I said I was interested in figuring out how to improve people’s privacy rights. Then, he asked me: “Do you care more about increasing people’s awareness of their privacy rights, or increasing people’s ability to have a say in it.”

He did a thought experiment. He said, “Imagine you’re walking down the street and I (Dr. Harp) saw you wearing a cool shirt, and I said to my friend, ‘Max was wearing this cool shirt today.’ Then let’s imagine that you said to me, ‘No. You can’t say that to her,’ and you (Max) get really upset because you didn’t want this information exposed.”

Reflection

I didn’t think there’d be any notable privacy breach. Unless I’m secretly on the FBI’s “Wanted” list and I don’t want to arouse suspicion, I suspect to the average eye, this wouldn’t be seen as a considerable privacy breach. I’d be hard-pressed to find nefarious or unauthorized uses for the information of “my cool shirt.”

There might be varying opinions on whether this constitutes a privacy breach, but does that make Randall obligated to not share that information? I think “having a say” doesn’t mean anything if all it means is “I have the power to determine what is private or not.” The goal of allowing everyone to have a say in it feels impractical and unnecessary and I think I care more about people’s awareness of privacy policies and rights than I do about their ability to have a say in it.

Why do I go into extensive detail about all of this? I do it to say that I discovered and learned to embrace my interests in the ethics of big data tools like Hedonometers, or Indigenous participation in environmental governance, or privacy rights. I realize that I want to address those topics and issues in some capacity in my career, no matter how disparate those interests seem from each other. I will have to find a specific niche and specialization soon, but ultimately, I developed more confidence in what interests me through the exposure to diverse types of research this summer.

My Research Questions

In my research this summer, I wanted to figure out how we could make privacy policies more transparent. My project was based on the presumption that transparent privacy policies are usable, so I tried identifying potential impediments to privacy policy usability. We defined a usable privacy policy as any policy where users can quickly and easily understand all the information within it (if they are willing to read it). I was curious: if users have to click through to more web pages to access all the information within the privacy policy, does that make the policy more wieldy and inaccessible as a result? I couldn’t fully answer that question due to the scope of my research project, but I aimed to move towards that question by first gathering a snapshot of external link counts across different types of companies and years.

Methodology and Discussion

I collected data from over 46000 online privacy policies with the help of my mentor to see if embedded link counts could be a marker of usability. We decided probably not. But we still collected that data about embedded link counts for certain business categories and years and tried to figure out what that data tells us about privacy policy usability. The information tells us which companies and years are associated with privacy policies that require the user to click through to more external web pages on average. And we were able to see which types of companies and years tended to be associated with more consolidated information on the same page.

We clarified that a caveat was we couldn’t infer a policy’s usability from external link count without further comparison points, but they at least offer another dimension to understanding a user’s experience with reading privacy policies. In order for us to determine how they affect usability, we would need to conduct future studies to offer more comparison points. For example, we could do a study that gathers the average time it takes for users to read certain privacy policies in their entirety, and then see if there’s a correlation between that and the embedded link count. Or, we could do a study that gathers all the information in privacy policies, puts it into standard 8 x 11 PDFs in size 11 font, and then compare page lengths with their respective external link counts. Here’s the link to my full research paper, as well as the link to my final presentation.

We identified many limitations in the way we collected our data. However, I’m currently unsure if my next step should be refining the data collection process in my project, or if I should shift focus entirely and explore an adjacent project that utilizes natural language processing to characterize the content of privacy policies. I’m asking myself: Do I want to continue investigating how to create more usable privacy policies? — And do I want to continue investigating that issue by looking at the external links within a privacy policy? The practical application of my research is that it helps to create better privacy policy reading experiences for users — policies that are easy to use and understand and thus, transparent. But I think my ultimate goal, in hindsight, was trying to find ways to make users more aware of the potential risks of providing their personal information. I don’t necessarily need to look at that issue through the lens of policy usability and readability. Perhaps the next project I want to pursue is gathering more intelligence on how companies are collecting, using, and selling personal data — and seeing if there’s a way to provide insight into that at scale.

Experimenting and Discovery

When gauging my interest in something, I ask if it speaks to me. Genuinely. I have to think about it. I have to be honest with myself, which I don’t think is a given. Sometimes x y z might be “speaking” to me because 10 minutes ago I overheard someone mention average mid-career salaries for x y z majors, or sometimes x y z might be “speaking” to me because my parents want me to do something “practical” and I’ve become really good at pretending to like the idea of, say, financial engineering, when deep down I may think, say, studying public relations is more interesting (or maybe I might not even know what is more interesting! Maybe the only thing I know is that financial engineering, in this example, is not immediately appealing to me).

How do you know if something is “speaking” to you? My opinion is: You don’t. I think you need to expose yourself to as many things as possible, and then you can get a sense of what things you like more, what things you like less, what things you feel more compelled to spend your time doing, what things you feel less compelled to spend your time doing, what things inspire you more, what things inspire you less, etc.

“More” and “less” are relative terms, so you can only make better judgments on what speaks “more” or “less” if you have more experience. You don’t want to have only one reference point to go off. Try many things. See what sticks. This way, you learn more about yourself and you discover passions you didn’t know you had.

Taking stock of your whole life, what experiences stand out to you? Which mentors and teachers have inspired you? Why do you think they inspired you? What particular moments (group project, one-on-one conversation, life event) stick out? Why do they stick out? What interests have you discovered that you want to keep pursuing? What new interests do you want to explore? As for me, this summer most definitely gave me more to take stock of.

Growing Personally

In addition to learning more about my interests, I learned how to program to scrape for particular information at scale and how to organize, analyze, and visualize vast amounts of data. I also had the opportunity to network, and I was exposed to cool projects that I’m inspired to take on after the internship end date.

I learned that:

- Research is a mindset. It requires having curiosity and being open-minded.

- Research is an attitude. It requires humility, patience, and grit.

- Research is an approach. How do I accurately scope the study of something and make sure it’s not too broad? Also, in any research project, it’s important to ask oneself what questions it can’t answer just as much as what questions it can answer.

- Research is being human. One has to listen closely to diverse sources (listening for inherent questions and key takeaways), and every possible project is a challenge to ethically frame key issues at stake.

- I can and should be more decisive. It’s okay to be. It’s easy to get stuck trying to figure out what to research, but ultimately I need to know when it is okay to just dive in and go with my heart.

- It’s okay to start small and in a humble place. What I don’t know far outweighs what I do know. And that’s okay. Wonderful actually.

This internship program allowed me to develop a greater interest in computer science, privacy rights, and data ethics. I developed skills in programming, data analysis, and visualization, and I met professors and peers who challenged my thinking and inspired me to pursue cool, impactful projects beyond the internship. This summer was also an opportunity for personal growth, as doing research allowed me to practice humility and become more open-minded, decisive, and less of a perfectionist.

I changed my major to Computer Science a semester ago, and this internship ultimately helped to solidify my interest in the field and the issues that it can touch. I come back to Clarkson with renewed energy to pursue a path that aligns with my values and goals, as well as share my passion with others.